“This nameless mode of naming the unnameable is rather good,” Shelley remarked about the creature’s theatrical billing. For the first theatrical production of “Frankenstein,” staged in London in 1823 (by which time the author had given birth to four children, buried three, and lost another unnamed baby to a miscarriage so severe that she nearly died of bleeding that stopped only when her husband had her sit on ice), the monster was listed on the playbill as “––––––.” “This anonymous androdaemon,” one reviewer called it. She didn’t put her name on her book-she published “Frankenstein” anonymously, in 1818, not least out of a concern that she might lose custody of her children-and she didn’t give her monster a name, either. Pregnant again only weeks later, she was likely still nursing her second baby when she started writing “Frankenstein,” and pregnant with her third by the time she finished.

“Dream that my little baby came to life again that it had only been cold, and that we rubbed it before the fire, and it lived,” she wrote in her diary. “Nurse the baby, read,” she had written in her diary, day after day, until the eleventh day: “I awoke in the night to give it suck it appeared to be sleeping so quietly that I would not awake it,” and then, in the morning, “Find my baby dead.” With grief at that loss came a fear of “a fever from the milk.” Her breasts were swollen, inflamed, unsucked her sleep, too, grew fevered.

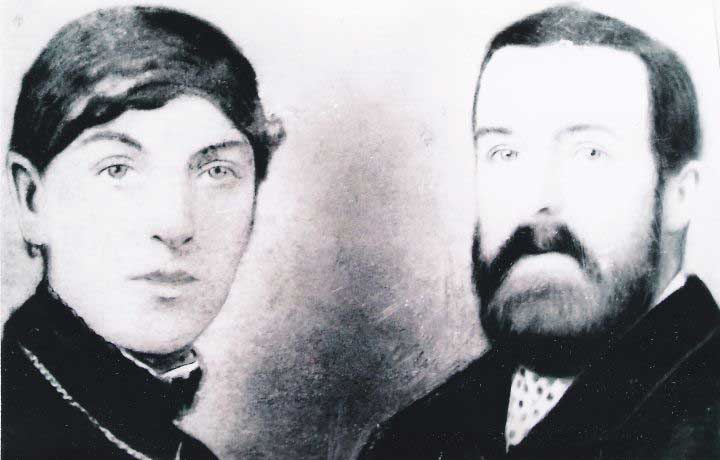

Mary Wollstonecraft Godwin Shelley began writing “Frankenstein or, the Modern Prometheus” when she was eighteen years old, two years after she’d become pregnant with her first child, a baby she did not name.

To hear more feature stories, download the Audm app for your iPhone.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)